Sanaz Fatouhi/ Essay: Ripples from the Unseen/

Your real ‘country’ is where you are heading, not where you are.

— Rumi (Barks 2004)

A few years ago I had the privilege of being on a panel with Sofi Basseghi. Our paths crossed then temporarily on the stage as Iranian women working in the arts in Australia. Yet, it was not until recently when I reconnected with her and stepped into the world she had created through her exhibition Ripples from the Unseen that I recognised a shared, perhaps less spoken about, path of some of our experiences as Iranian women of the 1980s. This period in my opinion could be seen as one of the most turmoil and trauma informed eras of remembered modern Iranian history. We were born at the cusp of the revolution as our parents were trying to make sense of a new government and its imposed rules and regulation. We were going to school to the soundtrack of the war between Iran and Iraq. We grew up learning to live parallel multiple often contradictory lives. We became really good at joggling between public and private, tradition and modernity, our needs and the expectations and rules of the society. For those of us who migrated to find a new home for our families for whatever reason, most of us were faced with a new set of cultural and social contradictions, and often dealing with severe culture shock.

Basseghi’s captivating exhibition encapsulates the many layers of the lived experiences of Iranian women of our generation and more. When I was approached to write about this exhibition, I found myself excited and at a loss. As an Iranian woman of the same generation as the artist and those represented in her work, as an academic and writer who has keen interest in the literature and art produced by the Iranian diaspora, I had way too much to say about this body of work. Yet for the scope of this space, I decided to simply express my own interpretations, at a glance.

In sum, in a series of video installations Basseghi explores the multitude of contradictory landscapes, ideologies and belief systems that the Iranian women of our era occupy and defy. The Substation is befittingly ideal for this exhibition and Basseghi has made brilliant use of it. Like the many hidden and unseen layers of Iranian women’s lives, each exhibit is displayed in a dark chamber, waiting to be seen and explored. Signposting the entrance to each room, in the tradition of Bill Viola’s slow-motion videos, are images of a woman submerged and floating in a liquid, each subtly gesturing and inviting the audience into one of the chambers. Entitled ‘Picked Women,’ I see this exhibit as the heart of the exhibition. It draws on the term ‘Torshideh’ which literally translates as something that has gone sour. Yet, the term has deeper cultural meanings. ‘Torshi’ in Farsi means Pickle and the term Torshideh over the centuries has come to refer to women who are left unmarried for whatever reason past a certain age. For something to be pickled, however, to be put in vinegar (or whatever else that can change its nature) and morph into something else, it needs time. It is not an overnight transformation and neither is the term Torshideh and its weight when referring to women. It has been a slow process – and the subtle movement of the women on the screen reflect and denote the slow yet powerful force of an almost irreversible transformation process for the way women are seen and related to in the Iranian culture. And from there each chamber for me seems to take on an exploration of some deeply ingrained aspect of the Iranian culture and its impact on the way women have come to create a sense of identity for themselves, and how they are defying the many labels and expectations imposed on them by centuries of cultural and social constraints.

I feel that Basseghi has cleverly mimicked the multiplicity of the layers and splits of Iranian women’s lives, experiences and sense of identity throughout the exhibition by the use of multiple screens. In two of the exhibits, Rebellious Fragments and Ascending Voices,the multiple screens allow us to glimpse deep into and hear the very private voices and stories of the women, their exploration of myths, superstition, and religious and other contradictory and controversial topics not usually openly discussed. Simultaneously we see the women in public spaces of transit, like cars and café where most of their public sense of self exists. In contrast to the intimate and close up shots of the women who narrate their very private stories, alongside these we are offered a parallel positioning of the women through distant, vast and often empty shots of the Iranian landscape. While watching the three screens simultaneously can be overwhelming for the viewer, who is trying to make sense of it all, it is a fair reflection of the multiplicity of the parallel identities that the women in Iran position themselves in and occupy.

Basseghi translates this also to the lives of those who migrated. In Elysium, we encounter Salme who migrated with her parents to Australia when she was four soon after the revolution. As Salme recounts her experiences of migration, of the culture shock, and a split sense of identity that she was exposed to as the result of moving to Australia, alongside it we see images of her in a garden burning wild rue, or floating and playing in the ocean. For me, the burning of the wild rue is a particularly Iranian tradition, a symbol that really binds us to a deep remembered sense of Iranian identity. It is deeply reminiscent of religious ceremonies and superstitious beliefs of guarding against evil eye. Contradictory to this, is the ocean that represents a connection to Australia and an Australian sense of identity. Similarly, here, the emphasis is the multiplicity of identities and spaces that women like us occupy, even when we have left Iran.

Yet, for me one of the most exciting and intriguing exhibits is the Elusive Paradise. In the chamber one has to pull aside and go through layers of sheer curtains, representing the many layers under which Iranian women’s true sense of identity are hidden, to get to witness Mischka’s story. Set in a winter garden and projected onto one of the sheer screens Mischka tells us of her honest views from the concept of Torshideh, to plastic surgery, to migration, and women’s position in Iran. Topics often not so frankly discussed in the public sphere. ‘Elusive Paradise’ feels like a safe space – a garden in which there is freedom to be and speak the truth and yet it is hidden. One has to pull aside so many different layers to get to it.

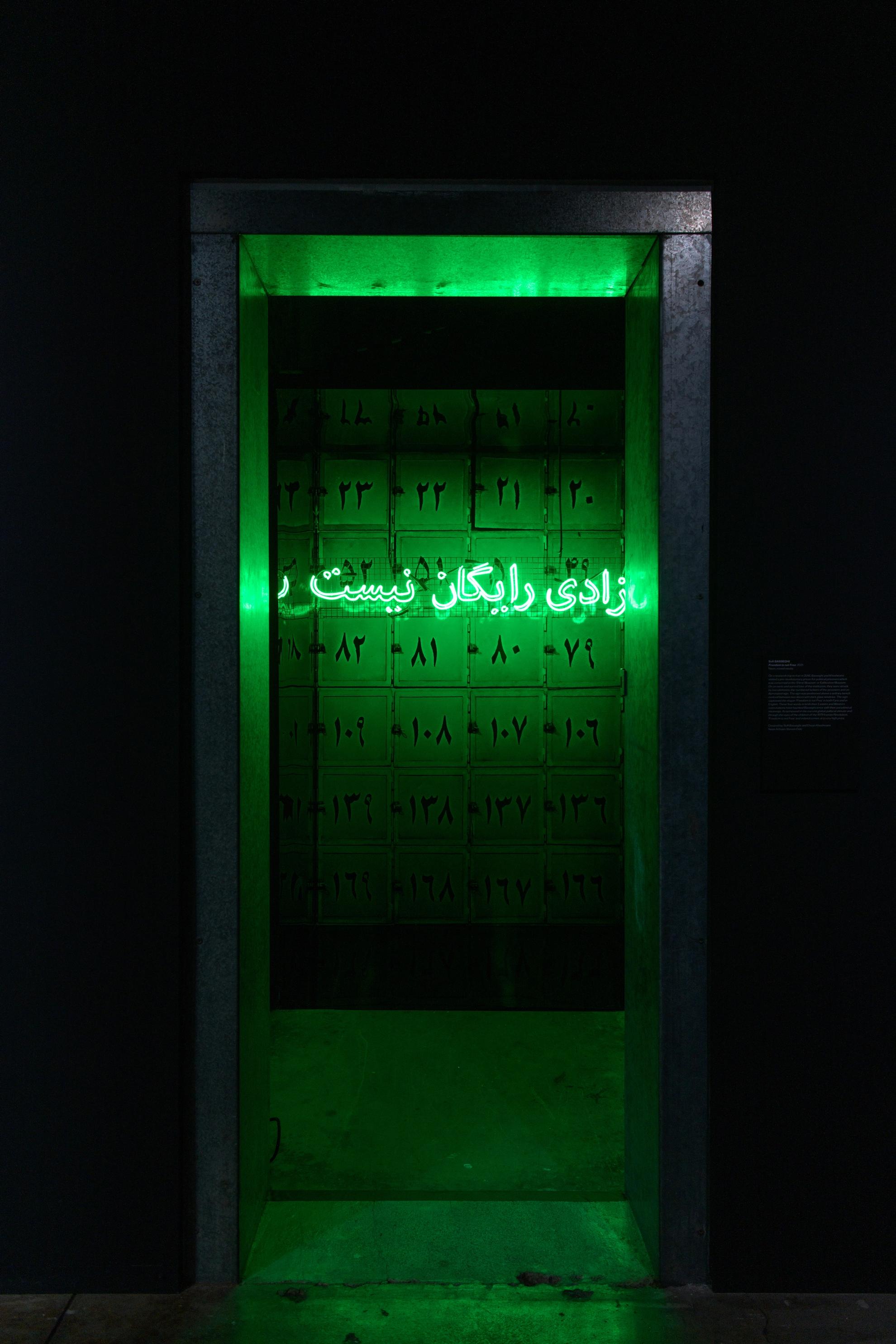

What sums up this exhibition for me is the poignant and ironic neon representation of a sign that Basseghi saw at a prison turned Museum in Iran which reads ‘Freedom is not Free.’ Here there are no multiple screens – no multiplicities of possibilities. It is just a neon sign set against the drab background of a series of closed cube doors with numbers on them that are prisoners’ lockers. Interestingly this is the first – or the last – exhibit depending on which way you decide to take on the exhibition. A stark reminder, perhaps, that despite it all, Iranian women (and men) have a long way to go before they can feel like they can freely express and expose themselves. While the generations who have come after us have had more freedom to express themselves, we all know that deep within there is a sign in a museum somewhere that reminds us to be cautious. And for now, we are destined to joggle the multiplicities so well represented by Basseghi until the pickle jar breaks.