Chloé Hazelwood/ Essay: Amos Gebhardt Spooky Action (at a distance) /

The concept of family in queer culture transcends the normative, socially engineered nuclear family unit. It doesn’t ‘require’ a cis-man and a cis-woman to procreate in order to be considered ‘legitimate’ or complete, nor is it defined by traditional relationship structures such as marriage. It defies conservative political rhetoric around what constitutes a safe and healthy environment for children to thrive in. The queer family is full of love, care and joy. It is ethically informed by a sense of kinship that isn’t limited by blood or conjugal relations, and functions as a lateral network of interconnected entities. While each individual within this ecology is celebrated for their uniqueness, it is not the kind of individualism that imposes (gendered) hierarchies on the family structure. Amos Gebhardt encapsulates the beauty and tenderness of queer familial ties in Spooky Action (at a distance), a major new exhibition encompassing four years of the artist’s practice.

Gebhardt introduces us to an extended queer family from Warrang/Sydney (via San Francisco): daddies Kelly Lovemonster and Spencer Dezart-Smith have relocated across the world to build a life with their baby son, Lexi. Given the mutuality of global queer scenes, Lovemonster and Dezart-Smith – who I came across on Instagram some years ago after attending an iconic Swagger Like Us party in San Francisco (run by the duo) – have seamlessly blended into Sydney’s vibrant and diverse queer community. Lovemonster identifies as non-binary and uses they/them pronouns. Dezart-Smith is a seahorse dad: a transgender man who gave birth to Lexi. This heartfelt analogy reflects the phenomenon in the animal world of male seahorses carrying babies, another counterpoint to essentialist definitions of reproduction.

In Family Portrait (2020), a triptych of still images from Gebhardt’s most recent three-channel video work Small acts of resistance (2020), the fathers flank the central image of their extended familial network. This centrepiece evokes a scene in botanical paradise, replete with candles, flora and an altar bearing offerings from family members. The fathers stand atop the altar holding Lexi, who is swaddled in gold cloth; the baby sleeps peacefully as his parents gaze lovingly at their new arrival, bathed in golden light. All but one of the surrounding family members gaze directly at the viewer, an act that is both endearing and empowering. They carry objects of cultural significance – we see conch shells, Turkish delight and Wiccan ritual tools. On the far left, there is an incarnation of The Magician, an esoteric tarot card symbolising the connection between spiritual and physical worlds. To the right, the family member looking toward fathers and child holds an evil eye amulet in their palm, a gift to protect Lexi from harmful energy.

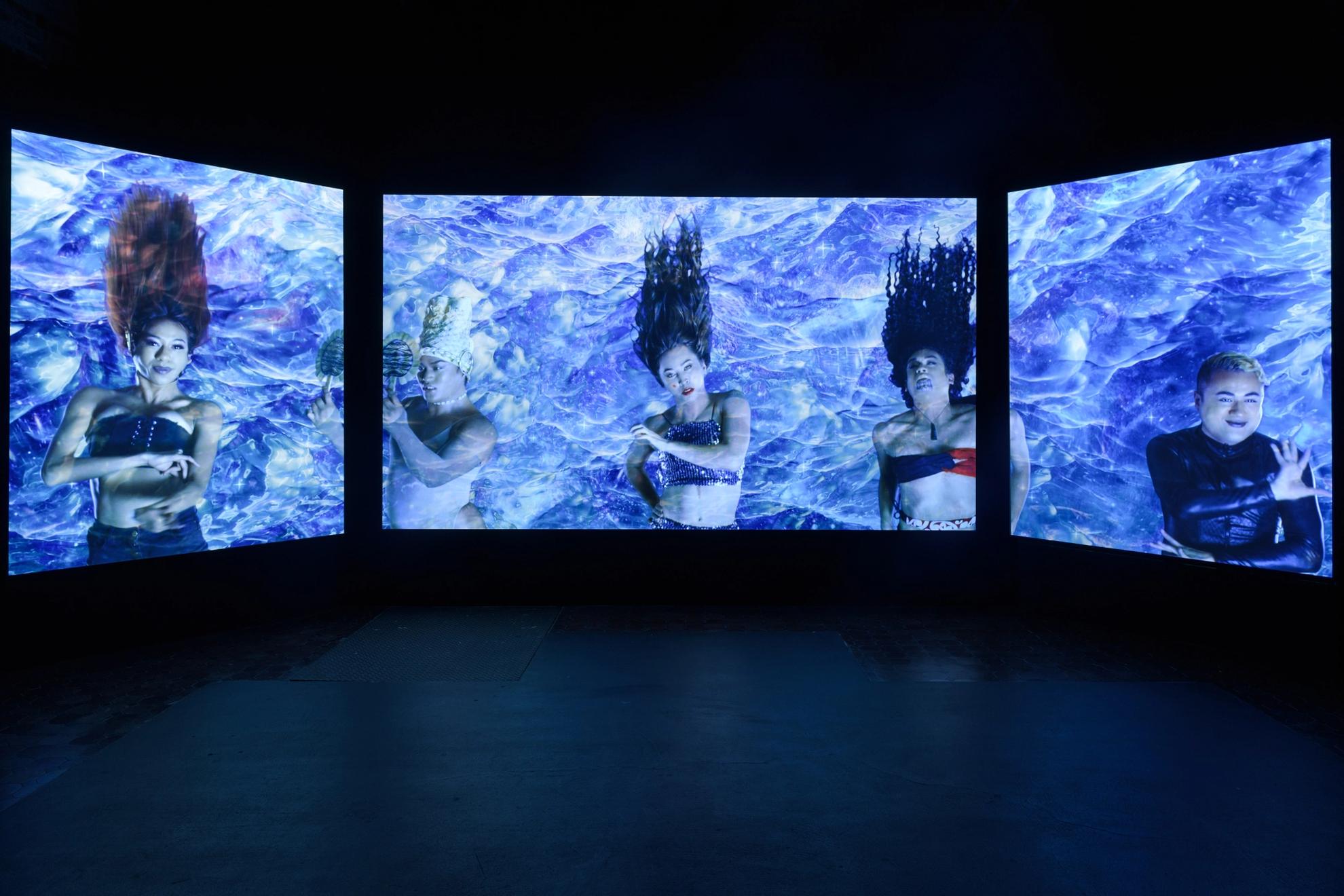

Small acts of resistance magnifies the fragile relationship between humans, animals and nature. Gebhardt weaves seemingly far-flung narratives together to convey the interdependence of all life on earth. Aerial shots sweep over a vast red desert landscape to reveal scarred lines in the earth; a long stretch of dirt road intersects to form the Union Jack and a cross, stark reminders of the ongoing harmful impacts of colonisation and Christianity to First Nations peoples. Ngiyampaa, Yuin, Bandjalang and Gumbangirr artist Eric Avery walks barefoot on Country, singing in language and playing a wistful tune on violin – this is a powerful reclamation of land and culture, an assertion of sovereignty. The virtuoso rises and is suspended in mid-air with his instrument, the sound of which vibrates through the gallery space as Avery watches over Country. Elsewhere, members of Warrang/Sydney queer collective House of Slé defy gravitational pull with a graceful weightlessness, making fluid movements while immersed in a twinkling ocean. Their expressions are soft, arms outstretched, beckoning the viewer to dive into their undulating waters. House Mother Bhenji Ra takes her place in the centre of the composition as the nurturing leader of the house. The collective advocates gender diversity, vibrant cultural expression and community-building through vogue and ballroom performance, with members hailing from across the Asia-Pacific.

The annual Christmas Island red crab migration is documented in mesmerising detail as these creatures make their way from lush rainforests to the ocean to lay their eggs in rhythm with moon phases. The crabs periodically reclaim spaces designated for human occupation – the built infrastructure of Christmas Island – to initiate the process of spawning at sea. Some crabs scale vertical walls, accidentally detouring from their ground-level journey. Others can be seen crawling over manicured front lawns. Roads across the island are closed to allow for millions of crabs to march unharmed, a rare instance of humans giving way to other animals. Gebhardt segues from this tropical setting to a familiar urban image: a flying fox colony taking up residence among the trees of the Birrarung Marr in Naarm/Melbourne. As pollinators, flying foxes play an essential role in the regeneration of native forests; in the wake of a global pandemic, they have been maligned and attacked, bearing the brunt of the spread of misinformation. While there is no evidence to prove that flying foxes directly transmit COVID-19 to humans, mainstream media is pervaded by calls to ‘evict’ them from urban areas, spurring on violent attempts to cull populations. Never mind that habitat destruction has led to critical food shortages and starvation – it is all too easy to scapegoat this benign species in the pervasive quest for dominion over nature. Gebhardt elicits an empathic response in close-up shots of a flying fox mother and pup huddled together in roosting pose – another species, much like our own, devoted to keeping their offspring safe from harm.

The catastrophic Australian bushfires of 2019-20 killed billions of animals and turned 18.6 million hectares of forest to charred earth. Many community members sprung into action to rehabilitate sick and injured wildlife, regaining a sense of purpose in the midst of immense personal loss. In one of the most poignant scenes from Small acts of resistance, Gebhardt enters the home of a wildlife carer as she bundles an orphaned joey into a blanket and bottle-feeds the vulnerable young animal. A resident cockatoo and two other joeys keep the carer company, members of an expanded household in which altruism facilitates harmonious relations between species. In another scene, dancer-choreographer Raina Peterson foregrounds the domesticated space via sentimental objects from their upbringing, which appear as mementos while Peterson performs in front of their family home on Gunaikurnai Land. Peterson negotiates white settler space – the quarter-acre suburban block – while proclaiming their diasporic Indian identity. Homes with utes and sports cars parked in the driveway serve as markers of the Great Australian Dream: a capitalist tenet that measures ‘success’ and ‘security’ in material terms. This mythology is subverted by a creeping sense of unease that compels us to question who is permitted to buy into these ideals. Who ‘owns’ these dwellings on unceded First Nations land? To what extent – if any – have reparations been made?

Evanescence (2018), a four-channel video work, was filmed on Boorong, Gunditjmara, Jardwadjali, Djab Wurrung, Barkindji, Mutthi Mutthi and Ngyiampaa Country. Through vast and varied landscapes: a rock formation, salt lake, lunette and waterfall – the artist centres First Nations sovereignty of the Traditional Owners of these lands, tapping into the concept of ‘deep time’. According to Apalech man and Indigenous Knowledge scholar Tyson Yunkaporta:

Kinship moves in cycles, the land moves in seasonal cycles, the sky moves in stellar cycles and time is so bound up in those things that it is not even a separate concept from space. We experience time in a very different way from people immersed in flat schedules and story-less surfaces. In our spheres of existence, time does not go in a straight line, and it is as tangible as the ground we stand on.1

Performers crawl and twist in unison, creating fleshy sculptural forms that oscillate in an endless feedback loop. They express an intimacy with each other and with their surroundings. The same flowing choreography is performed across all four settings, and I am reminded of Einstein’s dismissal of ‘quantum entanglement’ – or the ability of separated objects (tiny in scale) to alter their properties in relation to one another – as “spooky action (at a distance)”.2 Evanescence suggests that we are all entangled: physically, emotionally and spiritually. We are all parts of a greater whole and are representative of a fleeting moment in time; a blip on the radar of eternity. Human life is positioned as ephemeral in relation to the greater forces of nature that have produced geological epochs stretching back to the Big Bang (the inflationary epoch) and those that will project far into the future.

There are no others (2018), a single-channel video work, seems to hint at a state of transcendence: the surpassing of gender norms to reach new heights of liberation. Naked bodies tumble in ecstasy, cushioned by an infinite blue sky; each person featured expresses their gender identity outside of heteronormative categorisation. They illuminate the reality of gender existing along a spectrum, as opposed to the outdated male-female labels that are (still) assigned to bodies at birth. Gender-diverse people have been simultaneously made invisible and hyper-visible by major social institutions: government, health care, religion, education and the traditional family. The figures in There are no others have risen above moral outrage, fear and ignorance to unapologetically live as themselves in spite of a world that attempts to box them in (with damaging consequences). Gebhardt adopts stylistic conventions of historical nude portraiture; however, in this instance, the voyeuristic gaze and fetishism of “Old Master” European painting is absent. A dynamic of trust and reciprocity between the artist and their participants is palpable. The pulsating soundtrack, composed by Australian musician Oren Ambarchi, swells to an emotive crescendo as the final figure fades to white (a vision of what bliss looks and feels like).

Animal behaviour is a recurring theme in Spooky Action (at a distance), an attempt to deconstruct the philosophical position that human life takes precedence over all other living entities. A fascinating exploration of the mating rituals of horses is seen in Lovers (2018), a two-channel video installation that draws the viewer into the fullness of these late-night encounters, casting a cinematographer’s glance at what often remains unseen. Horses swirl around each other in a paddock, whinnying, neighing and canting in an elegant dance of desire. There is an eerie quality to close-up shots of the horses; their heads fill the screen and appear to be side-eyeing the viewer, as though aware of an alternate presence. At times, the play turns rough: a young stallion is momentarily rebuffed by a kicking mare after having attempted (and failed) to initiate sexual contact. Tension and suspense slowly build, giving Lovers the edginess of a thriller in which we are nervously uncertain of the protagonist’s next move. The photographic series Night Horse (2018) resembles a ghostly apparition of the herd in motion, a freeze-frame of their seasonal activity.

I circle back to the quotidian yet mysterious idea of time, and how it weaves through the exhibition. In working extensively with video, Gebhardt appreciates slow cinema for how it “leaves shots long enough not to indulge the pleasure of your cinematic expectations being met” so that viewers can experience “more complex ideas of representation and memory”. 3The artist achieves a level of complexity that is underpinned by a commitment to nuanced and ethical perspectives. Gebhardt approaches their role as creative facilitator with a deep understanding of the need to treat issues of LGBTQIA+ rights, climate change and environmental destruction with sensitivity, but also with an urgency that inspires action. Spooky Action (at a distance) is the artist’s clarion call.

—

Chloé Hazelwood is an arts writer based in Naarm (Melbourne). She lives and works on the sovereign lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Boon Wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin nation.