Ann Finnegan/ The Age of Aporia — The Rapids/

The Age of Aporia – The Rapids

by Ann Finnegan

“By aporia pure and simple,” so commences the existential complexity of Samuel Beckett’s The Unnameable. For the eponymous, hence nameless, character from whose point of view the novel unfolds, progress is fitful, uneven, a mixture of slow shuffle and the occasional run, at relatively break-net speed, through the surrounds of a dimly discerned twilight chiaroscuro, to which the character’s response is absurd, and often uncertain. The novel could well be an allegory for humankind’s existential relationship with water and the planet in general.

That said, The Rapids largely takes place in the bright light of day, in sumptuously green natural surrounds by the side of a river; however, like Beckett’s Unnameable, the images unfold nowhere in particular - setting out, or, rather, continuing on, from the contradictory starting point of aporia. There is a lot of water – and a lot of edits – as other image streams chaotically pour in.

Locations and time-zones multiply, as do historical periods: black and white footage from early cinematic newsreels, memorable snippets from Apocalypse Now, Coppola’s allegorical retelling of Conrad’s famous journey upriver in Heart of Darkness through the lens of destruction of the Vietnam War. At times the images pour like teeming water, and scenes to figure out where you are. Certainly water images of rivers and flows abound but the how and what and where are obscure.

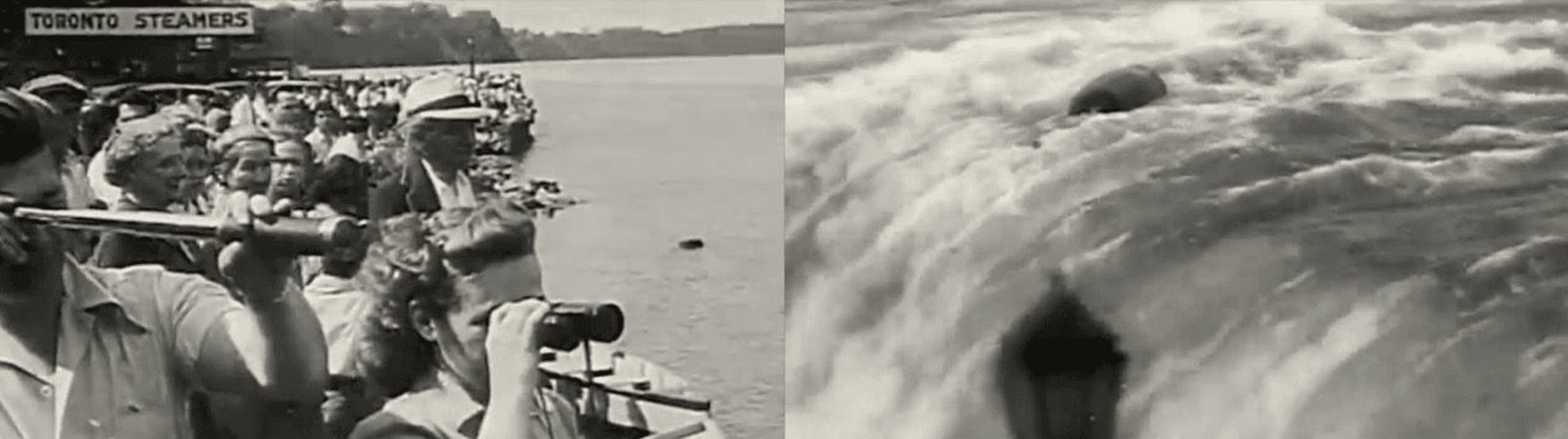

Human beings are doing crazy things, like being sealed inside a wooden barrel and being thrown over Niagara Falls. Cheap thrills. A large brown bear, astride a natural weir, during the salmon spawning season, better knows what to do, deftly catching the salmon as they leap upstream. Then a river elsewhere is in flood in murky black and white in old newsreel footage: houses are submerged, while debris dangerously whirlpools about. In contrasting footage a stately chateau perches above a more serene flow. Of their natural course, rivers evidently have their moods and modes.

With no explanation, the soundtrack directs the broken pace of these contradictory flows – establishing and de-establishing tempos and rhythms.At times a white clad female figure, drumming by a wide riverbed, has set up her kit on the sandy edge. Sonically the momentum builds to the equivalent of a guitarist’s steady riff, a cadence of complex driving beats, only to abruptly stop, cut off into a sudden silence.The drummer gets up, puts her back to the camera and contemplates the river. She sits down again, composes riffs set to a different beat. The tide is coming in. She hesitates again, stands up, turns, contemplates and dives into the river.She’s dressed in white. In that aspect her action recalls river baptisms and purification rituals, only nothing quite adds up, nothing fully makes sense.Then the tide comes in beginning to swamp the drum kit.

Visually, the image track matches the sonic contradictions. Every time you find yourself drawn along with the sound it abruptly cuts out, leaving you emotionally suspended, like a series of minor shocks.The sound is not behaving in expected ways, but it keeps seducing you in, and then leaves you stranded again.

The archival footage is a mixture of black and white, and old faded color of the film stock of the 1950s and 60s, pulling you backwards and forwards between the past and the present. Early black and white footage shows hundreds of people in bathing suits leaping from the banks of the Seine into the water, then a contradictory collage of a shot and the same shot reversed has a shoal of fish swimming across a human-made weir, swimming into each other, nature turned against itself, a commentary on the inanity of human intervention.

Why were those seemingly sophisticated Parisians diving into the water, en masse, a shoal of swimmers, for no apparent purpose, other than aimless pleasure? Other footage of an elsewhere has a man diving into swirling water, following a woman being carried downstream. It is unclear whether this is a rescue or they are enjoying some form of precarious fun.

It is hard to make sense of what humans do with a river: attitudes of reverence, fear, nonchalance, dominance multiple across the screen. At one point the viewer sees a portrait shot of the drummer, seemingly performing naked and therefore vulnerable on screen. Collectively the images form a contradictory collage of multiple responses to the rivers and the fresh water that sustains so much planetary life, for humans bringing pleasure, trauma, danger and destruction. Humankind, it appears, through this fragmented, yet highly accurate reflection of human actions and responses in respect of the planet’s rivers, is as much done unto, than exercising control over the rivers.

For every attempt at river and water management, every dam, weir and so forth, Nature has her own wayward, uncontrollable responses. Hence the title, The Rapids, conjures a mixed response of awe and fear.

Artist Quote:

My playing is spontaneously composed and responsive, and the surround sound design is wrapped into the vision. There is an exploration and exploitation of release and tension in the improvisation built from guitar, cello and drums, mixed in with live sound from the sites and nature - meditative but driving – almost an ecstatic response, which at times of intensity pulls back into the flow.

The film has a post-punk cut-up aesthetic that works with the idea of moveable collage or assemblage through the use of repetition, mirroring, meeting and diverging. It’s a construction made from the mayhem of the elements around us, and my love and usage of the archival. The archival elements sit alongside moments of serendipity and determine the atmosphere of my playing, charged with themes of decay, survival and fragility.

The Rapids is exhibited with 5.1 surround sound, as Apocalypse Now was actually one of the first-ever films to use it and in fact would make audience members duck in their seats because they’d never experienced sounds coming from behind them.

As with many of my projects, the work underlines the importance of place and is a meditation on the relationships with ourselves, each other, and where we are in time. In this visual and somewhat sonic ‘epic’, the water, the jungle, the landmass, responds as much to the global flows of history and nature, as it does to local places of lived experience and the state of the contemporary.

— Tina Havelock Stevens

MCA Quote:

Shadows fall across the Aguan River in the Phillipines, a place that stood in for South Vietnam to Cambodia in Coppola’s 1979 classic Apocalypse Now. Alive with the energy of that film’s upstream journey to madness, the mouth of the Aguan is now the departure point for Tina Havelock Stevens’ passage. Water is both the setting and a visual theme in The Rapids, as the artist spontaneously drums in improvised thrum and thrall to the outlet’s flow, intuiting the tropical environment as well as the site’s history as a playground for filmmakers who at once critiqued the chaos brought by US imperialist war and brought their own destruction to bear on the lush environment.

Havelock Stevens’ new work is a statement of acceptance and resistance to life’s unexpected flows, progressing as she modulates through the ebbing rhythms of Rorschached landscapes. She expands from the Aguan River to incorporate archival clips of other riverways, opening up toward a more timeless metaphorical power of water. Each shot has something to do with a larger creation: going backwards is difficult, and yet, in The Rapids, people and fish attempt to move against the tide. Rivers are emotional, ecological, spiritual. With their bends and loops, they move in only one direction; they can, like few other things, remind us of a common, restless humanity.

— The National, MCA 2018